By Nikita Ščiupakov

To understand the aim and meaning of our research, we need to give some background on our object – Lukiškės Square in Vilnius. During the last 30 years, the Lukiškės Square was one of the most discussed public spaces in Vilnius. Before that, in the Soviet era, the square was given Lenin’s name and a statue of the first Soviet leader was built there. However, after the restoration of independence of Lithuania, as the Soviet symbols were massively eliminated from the public space, the previous Lukiškės Square name and monument have been removed. However, it turned out that it is hard to reach a consensus on what new monument (and more broadly, what new meaning) should prevail in the square. One of the stumbling blocks in the history of the square is that it faces the infamous NKVD Palace, where hundreds of opponents to the Soviet Union were interrogated, tortured, and executed during 1944–1947 and on, meaning that Lukiškės Square became a symbol of terror and a place of commemoration after the restoration of independence.

The last round of conflict happened during the 2020’s summer when Vilniaus mayor decided to create a so-called public beach in the square, basically, to extend the possibilities of using it as a place for relaxation by installing beach chairs, volleyball court and other attributes of a beach. These actions of the municipality seemed to clash with the other common function of the square – commemorating the traumatic events of the 20th century.

The qulitative research aimed to understand how the Lukiškės Square and events surrounding it are perceived outside of Vilnius. Do non-Vilnius residents care about the future of the square at all? Maybe they have some certain opinion? Which socio-demographic characteristics influence it?

It could be expected that people from other regions would feel themselves somewhat alienated from Vilnius political events, but the research has pointed out that informants are well informed about the whole situation of the square and that opinions on the new beach differ a lot not only by the level of agreement/disagreement but by the premises of such views, too.

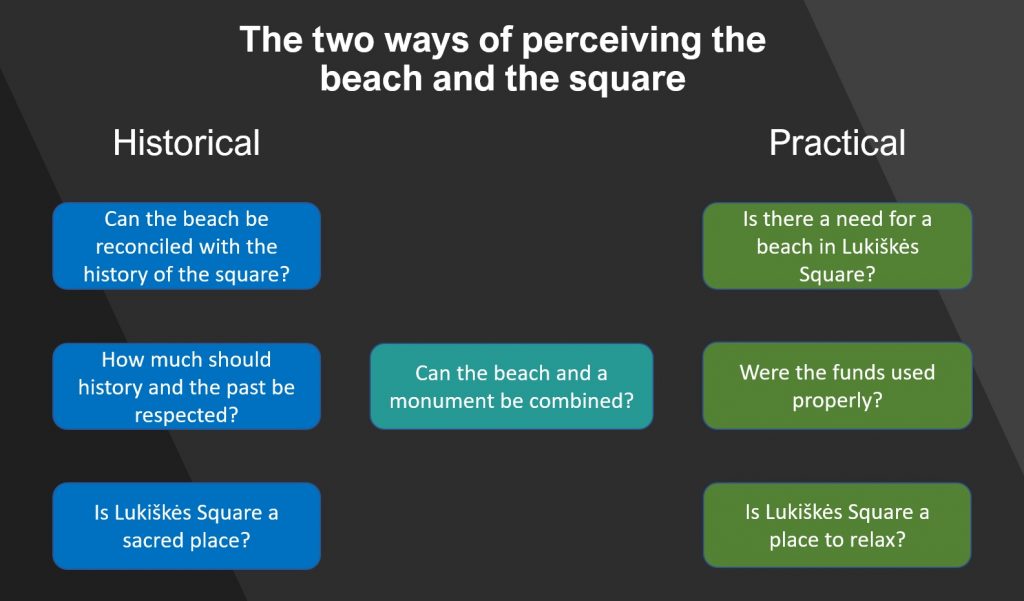

Mainly, we were surprised by the fact that many of the informants have not only historical perspective linked to some public narratives, but also a practical way of evaluating the square: they assess if they would want to relax on a beach in the centre of Vilnius and how would they feel near the potential monument.

However, one question remains unanswered – why the history of some public spaces, the Lukiškės Square in our case, can have such different meanings for the individuals of the same sociodemografic characteristics?

See the recorded conference report here [Lithuanian].

About methodology

In summer 2020 IIRPS VU (VU TSPMI) Students’ Scientific Society led by prof. dr. Ainė Ramonaitė carried out a fieldwork in rural areas of Lithuania. The initiative was a part of “Lithuanian National Electoral Study 2020” and its results were presented in the conference “Lithuania after the Seimas elections 2020” on 26 March, 2021. We decided to share some of the students’ papers in this blog.

The fieldwork took place in a small town (appr. 5000 people) and a village (appr. 300 people) on 5-6 August, 2020 (notably – before the second wave of COVID-19). The area differs from Lithuania as a whole in terms of its electoral choices in the Seimas elections in 2020 – conservative Homeland Union and Lithuanian Socialdemocratic Party were way less popular here, while the Farmers and Greens Union (former governement party), Labour Party and Liberal Movement gained significantly more votes than in the rest of the country.

The chosen fieldwork method was semi-structured qualitative interview. During the field research a team of 8 people took 20 interviews, usually, between 30 and 60 minutes in length. The researchers chose variety sampling. There were 9 males and 14 females in the sample (contrary to the researchers’ wishes sometimes 2 people participated simultaneously). Among them there were people with higher, vocational or high-school education, old age pensioners, students, workers and unemployed people. 4 of the informants fall in to the 20-35 age category, 3 to 35-50 category, 8 to 50-65 and 8 were older than 65.

Later, the qualitative interview analysis has been carried out in three rounds. Firstly, the interview transcripts have been coded into different themes (some of which are reflected by the topics of the conference papers). Secondly, each theme has been assigned two researchers who would then inductively code their theme independently from one another. Finally, the codes have been discussed, agreed upon and analyzed by both researchers.

Rich qualitative data gave students a better understanding about the inner logic, feelings and actions of Lithuanian people and they’d like to share it with the political science community.